Artist: A. Okhi Irawan

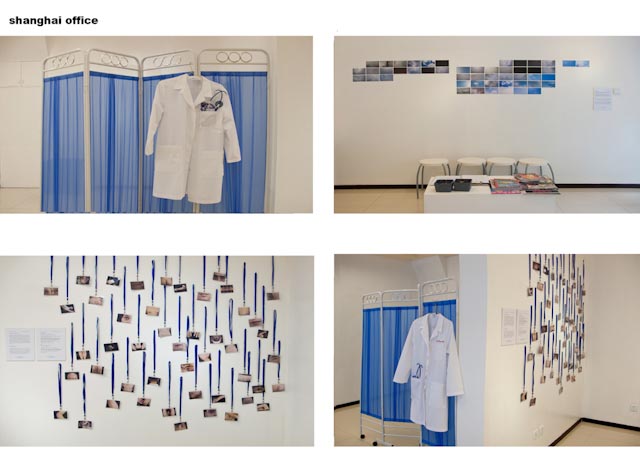

Artist: Abby Robinson / USA

index

PROCEDURE

People would sit in the waiting room (which I have created to look like one in a medical office), often striking up conversations—a way both of integrating contemporary art into the everyday urban experience and challenging the role of art as an educational tool for cross-cultural dialog and community cultivation. Everyone would fill out a medical/photo history questionnaire and present it when they were called into the office. In New York, quite a few participants thought I was actually a doctor, a holdover from the old clinic where the piece was installed. The Shanghai space was significantly different, more an art gallery/storefront combination. And in China, people were more apt to bring in their pets.

They would make their body part selection. Reasons for their choices varied: they liked/disliked a particular spot; they wanted a representation of a place on their body they couldn’t easily see; a significant other or friends characterized them by a specific feature; a body part reminded them of a family member or sparked a vivid memory.

A digital photo was taken in the studio, immediately printed out in the office, and placed in a plastic badge attached to a lanyard. The image was then worn around the neck like a VIP pass by the photo donor, with the badges creating further conversation among visitors.

Artist: Alessia Scena / Russia

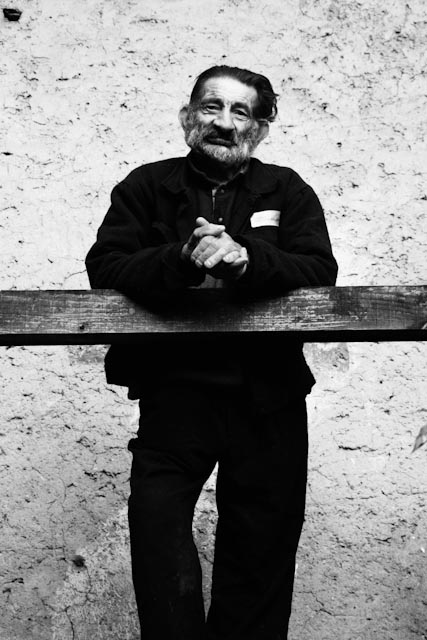

Art is a responsibility that we should all be aware of. Keeping our eyes open we can perceive that life is a constant becoming, intangible flow of events.

I see photography as a medium that can potentially stop this perceptive flow for a moment. And show us the pure and nude reality .

My photo story talks about the few last people who survived the l 2nd world war ,here, in my home town, l’Ossola, situated in the Alps, a land of farmers, partisans and smugglers, the first Italian Republic to be independent from fascism, unfortunately not many people in this area knows this. In the 50st, with the economic boom and the coming of the new era called “Benessere” ( wellness but i prefer to call it “good having”) a new spoiled generation literally erased what there was before :values, pride, solidarity with each other, respect for nature..

My photos are an image to these people who still live as if the clock has stopped back in the 40ies, working the land, living without wasting anything,.. and it s an invitation to my generation to learn from their strength and to readapt their lessons to our present world.

Artist: Alexandra Demenkova / Russia

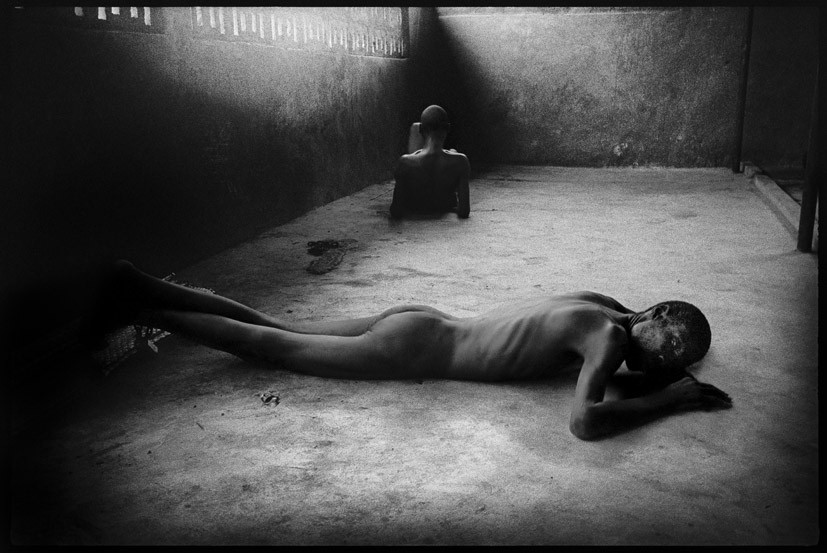

I started to do my first photographic projects in Russia, in Saint-Petersburg and in the region, near the town where I was born. It happened naturally because of the fact that I didn’t have an opportunity to travel at the time, and it turned out to be a great advantage – I knew about the places which remain non-existant for most people, thus, in a way, I photographed a parallel reality. This became a continuous quest for exploration – meeting people who live hidden and unnoticed by society.

This experience was eye-opening for me. It made me realise a lot of things, it made me think how fragile this world of relative stability created by our families is, how thin is the borderline between health, both mental and physical, and sickness; the normality of everyday life and misery; freedom and lifetime imprisonment. In the stories and in the lives of the people I saw hope and despair; all the possible emotions and situations that I heard or read of, now were not on the pages of the books, on a television screen, on a theatre stage, but here they were, in front of me, real, the first-hand experience of life, without any intermediaries.

Born in Kingisepp, Leningrad region, Russia, in 1980.

Graduated from the Herzen State Pedagogical University with a degree in Foreign Languages.

In 2000-2002 studied at the PhotoFaculty of the St.Petersburg House of Journalists in the group of Sergey Maximishin.

In 2005 participated in the masterclass organized by Objective Reality Foundation in Saint-Petersburg.

Alexandra focuses on social issues of everyday life, ranging from the homeless, migrant workers, lunatic asylums to ropewalkers, circus and street artists.

In 2007 joined Agency.Photographer.ru.

Alexandra received the Grand Prix of the Northern Palmyra, Saint-Petersburg, 2004.

She was a prizewinner of the Best Photo Correspondent of the Year (St.Petersburg, 2004-2006) including the Grand Prix in 2006; was commended at the Ian Parry Scholarship (2006); finalist of Descubrimientos, PhotoEspana, in 2007.

Alexandra took part in the 14th annual World Press Photo Joop Swart Masterclass in 2007 and was an artist in residence in Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten, Amsterdam, in 2008-2009. In 2008 she was a participant of Eddie Adams Workshop, Barnstorm XXI in the USA and is currently one of the students of Reflexions Masterclass (2010-2011).

She had solo exhibitions and took part in group exhibitions and festivals in Russia, Lithuania, Kazakhstan, Finland, Poland, UK, France, Spain, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Canada, Turkey, China and Bangladesh.

Continuing with the simplification of the Avada theme-specific markup to basic HTML while retaining the core content of images and text, here’s the next section simplified:

City of Home

Artist: Alina Kisina / Ukraine

I was born in Ukraine yet I always had a clear sense that I belonged somewhere else. 7 years ago I found what I was looking for in the UK and it has been my chosen home ever since. Going abroad meant adventure, excitement and the priceless opportunity to find my identity. We all want happiness in life and in order to find it I knew I had to answer the big question: who am I? The words “journey” and “path” are incredibly popular but what do they really mean? Then I accidentally discovered photography, or rather was discovered by it – it felt like being born.

Despite my new identity, a certain connection or even bond with Kiev, the city of my birth, still remains. Perhaps it’s a reflection of a deep understanding of its inner life, something I will probably never achieve in the UK as I missed out on a huge number of cultural layers while growing up in Kiev. Equally the past 7 years brought dramatic political and social changes to Ukraine and it’s becoming less and less of the country I left. However, I feel I am still in a very privileged position that allows me to look from a distance at something I know so well from within, a position of a stranger in the familiar. As a place I know and sense Kiev helped me create a consumerism- and cultural cliché-free photographic space, where the location and period are not getting in the way of seeing beyond the surface.

When I initially revisited Kiev in 2006 through the very first photographs of what is now the City of Home I was not looking for a clear definition of the place and the people but turned inwards, establishing the poetics as my reaction against the shallowness of its new commodity culture, while equally looking to express a sense of belonging and care. Gradually this process made me realise that the series is as much about Kiev as it is about a city – about man-made nature and its beauty and greatness which I contemplated with respect. I was looking at it and it was looking back at me with its layers of meaning, yet clarity and pulse.

The work became a search for something more universal, a deeper meaning, a way of grasping, experiencing and expressing a wider intuitive perception or concept: simply put that the world as we know it cannot possibly be it. Through my photographs I am questioning the limitations of what we know about it and ourselves and am looking for visual exit points to other possibilities, another dimension, another reality, another way of thinking. After all, our beliefs and understandings are shaped by the time we are living in, which to me by definition implies that we will never have the “full picture”, whatever that is. Nonetheless, searching for it feels like discovering a secret inside a secret – frankly it feels ecstatic yet perfectly natural.

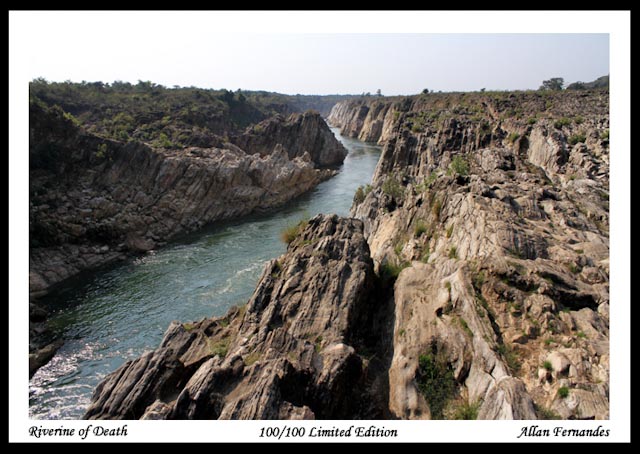

Allan Fernandes is an Indian Photographer of Goan native and Portuguese ancestry. He works in different photographic genres including portraiture, and is best known for his expansive landscape photographs that delve into the history of human society and their co-relation to the present. Structure, symmetry, design and composition are center-stage to all his photographs; often encapsulating the viewer to a soothing, calm, serene and divine atmosphere.

An alumni of St. Andrew’s, he studied photography at the National Institute of Photography.

=

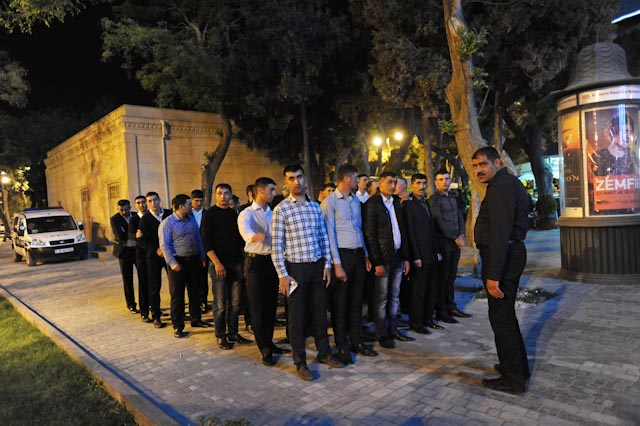

Tomorrow Belongs To Me: Post-Soviet Petrostate of Azerbaijan

Amanda Rivkin

“Tomorrow Belongs to Me” is an exploration of life 20 years after the fall of the Soviet Union in Azerbaijan and 17 years after “the contract of the century” to build the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan oil pipeline delivering Caspian crude to the West via the Turkish Mediterranean port of Ceyhan was signed. Part fantasia and part broken dreams, the post-Soviet petrostate of Azerbaijan is a case study in the broken promises of political transition and the enduring nature of political circumstance, the security apparatus and the persistence of culture.

Amit Chakravarty has made his passion into a career. His photographic journey is very personal, and is his life. He documents his feelings and environment, which is in an ever-evolving state, it’s very much a journey. Whilst he does editorial shoot for a living, his personal projects are normally where his roots are.

Major milestones in his carrier till date has been getting an award in Ramanath Goenka Photo contest in India – 2006,followed by an exhibition in Pingyao International Photography Festival in china – 2008 , screening of photographs at Kalaghoda Festival in Mumbai-2009, Delhi Photo Festival in India- 2011, screening at Bursa Photo Festival in Turkey-2011 and Open show in Mumbai – 2012.

MES SOUVENIRS

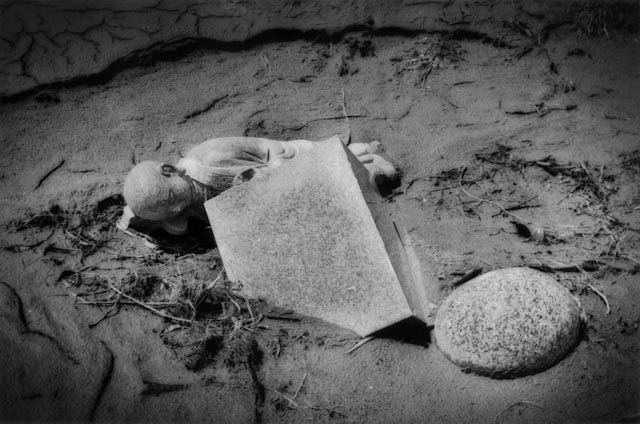

Artist: Anil Eraslan / Turkey

This project began last year.

After all these years passed from the childhood, I wanted to recreate the images that

remained in my memory. It’s a return to my childhood, places, and intimate moments as a psychoanalytic research

to myself.

The importance I give in recreating these moments is because of my personal

wonder to show myself a part of my past with my vision of today and

let the spectators also take out their hidden images in their memories.

The series consists of 12 photographs in silver color that will be exposed

As a photographer, he participated to many exhibitions in Turkey and in France and is awarded by Geniş Açı Young Talents Project, Nancy Jazz Pulsations, Px3 and Center of Fine Arts in Fort Collins in USA. During 3 months from october, he will stay and work in Berlin as a CEAAC (Centre Européen d’Actions Artistiques Contemporaines) residency artist in Berlin.

Artist: Anna Aseeva

In all my works i try to show ” another “side of reality.i try to open elusive, mystery of people, things, spaces.i make invisible visible. sometimes its a dark sides, sometimes white,but it always contrast of that lies on a surface.

some words about technical moments of my works:

i I have no single stile . I don’t like a glamour and glossy in art. I take my pictures with many kind of cameras, from handy to ancient cameras . As I started with films, i still have more satisfaction from black-and-white chemical process. I often use outdated materials: paper, film , chemicals. I like to make any size pictures despite of that modern photography tend to big size pictures.

INTO THE SILENCE

Artist: Carlo Bevilacqua / Italy

A new utopia? A distant reality? Forget it. Here’s another consequence of the din of the modern world. Hermits have not disappeared. They are a growing and fascinating phenomenon, instead. They don’t indulge in the search for isolation for social or personal ambitions, neither it’s a matter of misanthropy. They hold graduate degrees and well established jobs. Most of them come from a religious background but there are also many laymen amongst them: architects, doctors, directors, writers, teachers. Regardless their own habits prayer, meditation and silence are crucial to them. Some of them have an e-mail address, some others completely refuse technology. Some of them pose for pictures while others do not grant an interview, even an unrecorded one. Some use the voicemail as a filter for calls, others answer the phone just once a day. Laymen or religious, Catholics or Orthodoxes, shaman healers: these are the contemporary hermits whose powerful and fascinating effect lies mostly in their presence and witnessing. Sometimes they live isolated in small apartments in the heart of our cities but most often they choose to dwell in the woods or in small villages. The early pioneers of the solitary life made their first appearance in France, Canada and Italy at the beginning of the 80’s. The western hermitage – after the extraordinary flowering of the early Christianity age and of the High Middle Age – disappeared from the 19th century to the first half of the 20th. However from the beginning of the 60’s, someone have begun to reconsider it as a lifestyle, not a mere religious choice. A little, hidden but lively strong world far from the false myths and needs of our unnecessarily dizzy society.

Into The Silence is the new Carlo Bevilacqua’s long term photographic project about the contemporary hermits.

He has met and spent time with dozens of very special people who have chosen to live in solitude for religious reasons, others because they wanted to stay in touch with nature, others for love … In short, each with a different history and motivation.

He went to Mount Athos in Greece, and to Wales. He spent weeks in an Italian hermitage, at monastery in the middle of nowhere of Georgia’s desert, in the desert of the California, in France, in Southern India and Darjeeling,

He met secular hermits, Christian, Orthodox, living in caves, in cemeteries, in TeePee, fascinated by their extraordinary stories of surprising humanity which strike for the radical choice of lifestyle and for the beauty of life that flows from it.

Images from Into The Silence have already been displayed in various international festivals and galleries such as

Encontros Da Imagem – Braga (Portugal)

Open Salon Photography 2011 – Gallery Huit – Arles 2011 (France)

Photography Open Salon 2012 – China House – Kuala Lumpur (Malaysia)

Fotonoviembre 2011 – Atlantica Colectivas – Tenerife (Spain)

Taylor Wessing Prize 2011 – National Portrait Gallery London ( UK)

SpazioFarini6 Gallery Milan PhotoFestival 2012 (Italy)

Cortona On The Move Photofestival 2012 (Italy)

Artist: Cath. An / France

She found her niche in art history, then architecture from where she got a degree.

“Her native land is a land of sentences picked up along the books she read or the walks she had. From these, she extracted, in her own special way (maybe due to her Croat origins) poetry.

She lives on words ; she lets them settle in her mind, under the shape of some writings or some photos. She turns these gushing emotions into photos. Cath. An. has learnt from her architecture studies precision in constructing anything – whenceher «series» which are playful variations of lines and shapes. The core of her quest is not here yet. It lies more in her will to suggest a presence by the absence of a subject.

And especially because she wants to share what she feels from the quivering behind appearances under the veil of light.”

Catherine SIMON, Historian of Art

NATIVES: THE DANES. 2008

Artist: Charotte Haslund – Christenden / Denmark

In my work I strive to challenge and deconstruct the mechanisms and representations that reflect, form and reinforce stereotypes.

With Natives: The Danes I chose to reverse the colonial gaze. To make ethnic Danes the object of the gaze, in the same way that Western visual representations have stereotyped others. Historically the links between Western colonialism and the invention of photography are well documented. Photography was seen – and all too often still is – as an objective and scientific medium. Its alleged transparency and direct registration of reality often distracts from or disguises the ideological role it plays.

As far as I’m concerned – and I’m not alone – photography has been an obvious tool of colonialism in representing ’primitive’ peoples and all that Western ’civilisation’ has to offer. A virtually Darwinist discourse of cultural – and racial – evolution in which representations, including photography, continue to play a central role in the global media.

Artist: Corrine Silva / United Kingdom

The plate of Africa is moving at a rate of 1cm per year against and underneath the Eurasian plate. In 10 – 15 million years, the Mediterranean Sea will no longer exist.

The landscapes of southern Spain and northern Morocco share many geographical features including climate, flora and fauna, as well as a history of trade, migration and invasion. In 711, Berber tribes straddled the Mediterranean Sea, at its narrowest point only 14 kilometres, to build a Muslim empire. The Muslims were eventually forced out in the 1400s but connections continue; during the last century Spain further colonized northern Morocco. Today many Moroccans provide cheap labour for the agricultural industry in southern Spain, and those that are able invest money in property along the rapidly developing northern Moroccan coast.

To consider these connected and overlapping Mediterranean landscapes I travelled along the northern Moroccan coast from Tangier towards the Algerian border, and made a series of landscape photographs. I then contributed to the shaping of the Spanish landscape by installing three of these images on 8 by 3 metre billboards in specific locations in the region of Murcia.

The billboards reform the Spanish landscape. By photographing my installation, I fix it in the representational space of photography. The photographs turn my physical intervention into a permanent one, elaborating upon the act of placing one landscape inside another – the southern hemisphere into the northern. By visually representing the two as interlinked and interchangeable I create a space to contemplate not only their shared topography but also the complex web of their ongoing connection of trade, mobility and colonisation.

Imported Landscapes forms part of an ambitious project in which I use photography to look at, translate and produce landscapes that lie on the ‘political equator’. Based on a revised geography of the post-9/11 world, a line drawn from left to right across a world map intersects at three key contested desert territories: the Mexico USA frontier, southern Spain and northern Morocco, and Israel/Palestine. This political equator, conceptualised by architect Teddy Cruz, is a destabilisation of historical ways of mapping and colonising: it suggests a different politics of space.

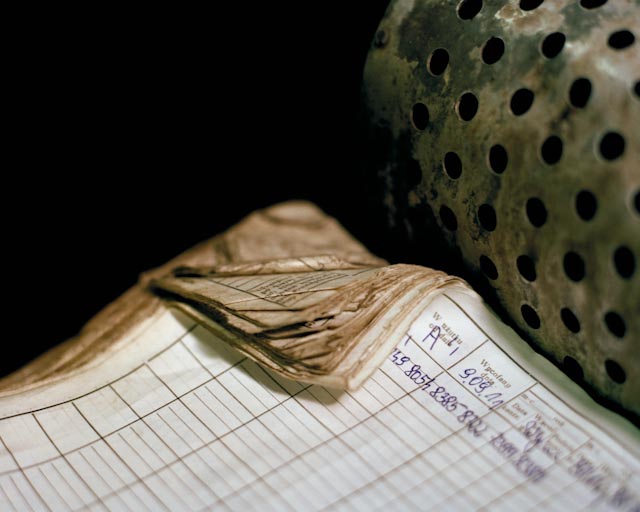

Coal Story’ (2011)

Artist: Darek Fortas / Dublin, Ireland

The project is a result of an extensive photographic engagement with the two largest coal mining companies in the European Union located in Silesia, the most industrialized part of Poland.

‘Coal Story’ combines contemporary photography and archival research dating back to the 1960s, when Poland experienced significant economic and industrial expansion. In the early 1980s, coal mines were a major site of struggle and resistance against the communist regime. Workers’ protests resulted in the creation of Solidarity – a workers’ and citizens’ movement under the leadership of Lech Walesa. The coal miners actions eventually led to the collapse of communism and the end of the Cold War.

‘Coal Story’ highlights the social and political capacity of the miners and evokes the history and aftermath of the legendary Solidarity movement. This exhibition poses important questions that are associated with Solidarity’s values; the movement’s legacy and its influence on contemporary Polish society.

Artist: Diego Lopez Calvin / Soria Spain

Graduated in Information Sciences, Complutense University of Madrid. 1991. Stills Photographer and Camera Operator working for Film and TV Producers. He experiments with photosensitive emulsions, pinhole cameras, solargraphy, video and internet.Diego started solarigraphy 11 years ago, actually he has launched the project “Time in a Can” where 50 artists from 15 countries are working together are working with solargraphy.

Artist: Eleanor Leonne Bennett / United Kingdom

Eleanor Leonne Bennett is a 16 year old internationally award winning photographer and artist who has won first places with National Geographic, The World Photography Organization, Nature’s Best Photography, Papworth Trust, Mencap, The Woodland trust and Postal Heritage. Her photography has been published in the Telegraph , The Guardian, BBC News Website and on the

cover of books and magazines in the United states and Canada. Her art is globally exhibited , having shown work in London, Paris, Indonesia, Los Angeles,Florida, Washington, Scotland,Wales, Ireland,Canada,Spain,Germany, Japan, Australia and The Environmental Photographer of the year Exhibition (2011) amongst many other locations. She was also the only person from the UK to have her work displayed in the National Geographic and Airbus run See The Bigger Picture global exhibition tour with the United Nations International Year Of Biodiversity 2010.

Artist: Eric Bouttier /Paris France

Eric Bouttier lives and works in Paris. His education in cinema and photography lead him to wonder about the possible links between still pictures and moving images, fixity and movement, by exploring various manners of giving to see an image and dividing it. His artistic work use various mediums (photography, video) and supports monstration which are registered halfway between photography and projection : photographic prints (“DES PAYSEMENTS”, serie in B&W in 7 shutters, 2005-2011), diaporamas (“Calm Moments”, series of 71 photographs and projection, 11 minutes, 2010), video installation (“From here”, photographs and sound vidéo and Super film 8, 8 minutes, 2007).

« Most of the time, we are in the recording in extremis scenes to which the author assists. This contributes to give to the images their singularity: this placement between instantaneity and deployment » Emmanuel Madec, galerist (Le Lieu, Lorient, France).

Artist: Erin Mulvehill / New York USA

my work aims to explore the human connections and subtle nuances that whisper into the ear of our every day. much of my work is rooted in the ideas of mind, body, seamlessness, and time. this is largely because my deepest beliefs lie in the principles of buddhism, the integration of art and life, and the preservation of beautiful moments. i am nomadic by nature and am inspired each day by the nothingness that resides in all things.

Artist: Fie Tanderup / Denmark

The turning point in my artwork is transformation. As a photographer I try to push my photographs in another direction. For me photography is about entering a space and not just about a glossy surface. Painting with the eye is what I try to do in my photographs. The portrait and the self-portrait are examined in a new way of letting the spectator move into the unknown among

st embroideries and dark holes.

Letting dreams float which makes us ask a question to the world once more is occupying me as an artist. I circle around telling a mysterious story. It is like a still from a movie that does not exist anymore with persons caught in their own picture world. My photos are undermining the truth-value of photography in establishing another reality. A sort of parallel reality is created where new stories are about to happen in a circular time.

It is an open space vibrating between reality and dream. In my photos a kind of overlapping between past and present and a kind of displacement between time and memory are taking place. I am constantly exploring an area between reality and imagination – between the spectator and the place and at the same time it is a dramatization of the situation.

I am establishing a poetic universe based upon atmosphere. The persons in my photos are in a state of dreaming. The twilight is underlining the sense of a magical reality where the spectator is invited into a vibrating, poetical space as a co-poet inside the picture.

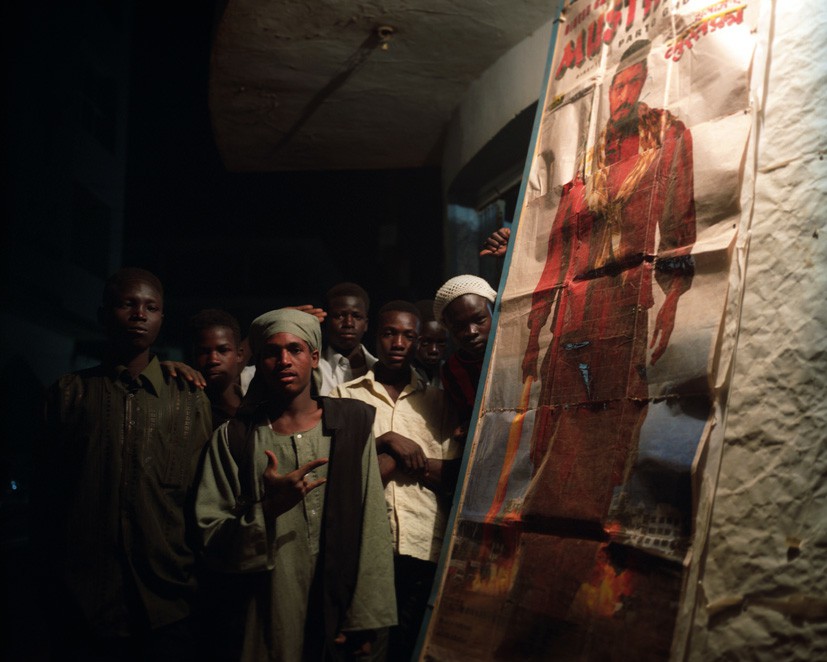

Cinema in Sudan

Artist: Frederique Cifuentes / France

The project is based on photographic research carried out in Sudan. This project explore the relationship between architecture and a cultural tradition as seen through the cinemas of Khartoum.

The project relied on my recent experience in Sudan covering the history of cinema through the life of the pioneer filmmaker Gadalla Gubara .

My portfolio shows how I conducted my work in Khartoum, Sudan. I was using the Mamiya 6 x 7 medium format, still camera.

Khartoum, in Arabic: al-Khartûm, meaning «the trunk of elephants», is the capital of Sudan, it stands at the junction of the White Nile, flowing from Uganda, and the Blue Nile, from Ethiopia. The city and its surrounding districts constitute an agglomeration of at least four million inhabitants. The city was founded in 1823 by Mehemet-Ali Pasha, viceroy of Egypt, to take advantage of a position considered to be of strategic importance. After being besieged many times by British and Egyptian forces involved in putting down local uprisings, the place was in a very poor state of repair. From 1910 onwards, it was entirely rebuilt to the plans of a British architect and became, from then on, the capital of Sudan.

What is Khartoum like today? What are the influences of British and other styles of architecture which contribute to Khartoum’s special character?

It is through the cinemas of the city that I have chosen to analyse the relationship between the physical environment and those who live there. Stepping through the doors of these historic buildings, the visitor can recognise social and cultural forms that stem from knowledge and technical means far beyond those of an Arab or African town.

Over the years Khartoum has become a city in perpetual evolution resulting from the interaction of people with their material environment. The cinema, considered as a representative form of the audio-visual arts and of architecture, is an element of urban life that can be seen to highlight both cultural heritage and collective memory.

Going to the cinema in Khartoum can be a journey in itself. The cinema can show us a world of its own, with performances in the open air beneath the stars; it’s a voyage of discovery into the history of the country; an encounter with a unique cultural experience.

Nowadays Khartoum cinemas offer mainly a selection of Indian, Bollywood films with the occasional American production thrown in. Set up in the 1940’s and 50’s by the British, cinemas were then frequented by the European population, by Sudanese Jewish families and by middle class Sudanese who were well enough off to do so. All the classic titles of the day passed on the silver screen, given two performances, one at 7pm and another at 9.30pm.

The external shape of these buildings varied according to the district and the year of their construction. Khartoum still has a dozen or so of these open-air cinemas still functioning mainly to provide entertainment. The facilities are used specifically to provide for a particular public.

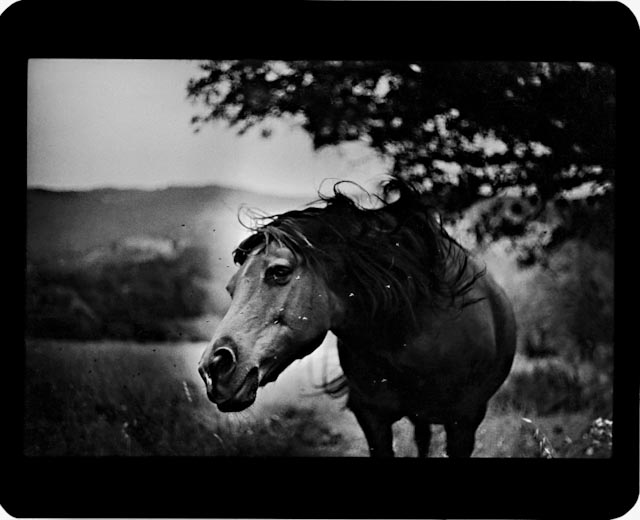

Artist: Giacomo Brunelli / Italy

I have been working on the series of animals for five years and with them I want to photograph my own reaction in their presence.

When I was a child I used to spend time playing with animals and I think that is why I push the lens often to its closest point of focus, almost touching the subject and forcing flight or fight from the animal, which is when I then re

cord its reaction.”

All the animals I photograph are found in the backyards, small villages, fields, and farms and I call the way I work “animal-focused street photography”.

Once I see an animal that I want to photograph, I try to ignore it then I run after it which usually gains a response; sometimes I just stare at it and see what happens. Their reactions are different, sometimes they are curious about the camera and sometimes they get scared about the noise of the shutter. When I am dealing with dead animals I pick them up from the ground and place them where I think the setting works. In this case my interaction with the animal is a way to give purpose to something that it no longer has

Artist: ishola akpo / BENINOIS

Born in Ivory Coast in 1983, Ishola Akpo is an artist and photographer multimedia. He works about digital images to create his own visual universe with colors and figurative forms and then renew the “collage” practice. He claims their formal artificiality to reveal the depth of their sense. Deliberately constructed, these images refer to African realities. Mixing his themes, he explores their metaphors that still allow multiple levels of interpretation. He received an award from the Heinrich Boell Foundation in 2010 and he’s the finalist of the session FreeLens webdoc Photography Festival in Toulouse in 2012

Artist: Jacqueline van der Venne / The Netherlands

Jacqueline van der Venne has studied both graphic and advertising design, illustrative arts, and photography. In 1987, she graduated from the Art Academy in Maastricht, and has since seen several years of steady employment in the field of graphic arts and design. Since 1982, Jacqueline has exhibited her work both in The Netherlands and abroad.

Her work includes

photography, paintings on canvas and drawings on paper, strongly combined with the use of new media. Jacqueline works as an artist, graphic designer, photographer, web designer and lecturer in art & design. In 2005, she earned her teaching degree and has taught at both primary and secondary school, where she offered courses in drawing, arts & crafts and CKV (arts and cultural education).

People in all possible aspects are central to her work, in which she searches for the ultimate shapes and colours to make her art vibrant and dynamic. Beauty is the essence of her art, and communication through it is her main theme. Jacqueline finds that a successful work of art is one that evokes feelings that may be either positive or negative.

Jacqueline van der Venne lives and works in the Netherlands

Artist: James Whitlow Delano / New York USA

I found myself in Rome, Italy on 11 March 2011, when the black tsunami struck. The return flight I took the next day turned out to be one of the last commercial flights from Italy into Japan.

I had already begun to lay down plans on how to get to Tohoku before leaving Rome. The flight landed at 2pm in Narita. By 3am, I was heading north in a mini-van with trusted friends along the far, Sea of Japan coast of Honshu because of rumors about an imminent nuclear meltdown in Fukushima.

There would be an explosion at Fukushima Daiichi that rainy day which pushed a massive amount of nuclear fall out to the ground, preventing it from being carried away by the wind, resulting in the need for the nuclear no-entry zone. We were unaware of the severity of the situation on the other side of the island as we focused on getting over to Iwate Prefecture safely. The car was loaded with jerry cans of extra fuel, drinking water and food, all of which, we had been told would be in short supply.

By morning the rain had turned to snow. In the center of the island, gasoline was being rationed and lines of cars stretched for kilometers. Residents were so desperate for fuel that, after waiting all day long, they would park their cars in lines for the night and return to them in the morning. It was decided to hire a taxi which used liquid propane gas because that fuel was plentiful.

Supply lines in Japan were breaking down. Runs on food and water left store shelves empty and that meant little or no bottled water for sale at a time when radioactive iodine from the unfolding nuclear crisis was being detected in water supplies.

The snow intensified in the tsunami zone. I wanted to climb right out of the taxi window, so intense was the desire to record the unthinkable. Cars were folded like soft drink cans over bridge railings 15 meters above the water, trees were impaled through 3rd floor windows and boats were even deposited on rooftops.

Survivors shuffled through the mud and snow in a state of shock. Soon we joined these shuffling masses, feet soaked with freezing cold black mud carried in by the tsunami. Moving inside provided little relief because inside evacuation centers temperatures hovered below 10 degree C, which leaned heaviest on the very young and the very old. The survivors gathered in family groups on blankets striving to regain a modicum of privacy in a twilight pall of anemic lighting underpowered by gas-powered generators (again fuel was in such short supply). No words were necessary for communication. It was there I first encountered a peculiar infinity-stare, born of worry, cold, hunger and lack of sleep. It would become a familiar expression in the time ahead.

Soon, though, the crisis at Fukushima Daiichi began to eclipse the tsunami disaster further north. Last week a nuclear expert expressed concern that the tsunami and explosion-weakened structures could collapse in one of the seemingly ceaseless aftershocks here, tipping out radiation on a scale that would dwarf Chernoble, over a year after the multiple meltdowns. It took the Soviets just eight months to construct a concrete sarcophagus completely sealing that reactor. The reactors at Fukushima remain exposed to the open air. And so this crisis has not ended by any means.

*****************************************************************************************

On 11 March 2012, the one-year anniversary, a family stood dressed in black on an empty plot in Ishinomaki, Miyagi Prefecture, where their home had been swept away. One of them was holding a little Buddhist monument dedicated to a lost family member. I thought to myself, “I don’t want to do this”, as I approached to ask to make a portrait, but I knew I had to do it.

Our eyes met and smiles broke out. They offered me a couple of digital cameras so that I could take their photographs. They asked me to stand among them and be photographed. We parted laughing. We all laughed together that day, exactly one year after the tsunami had changed our lives forever

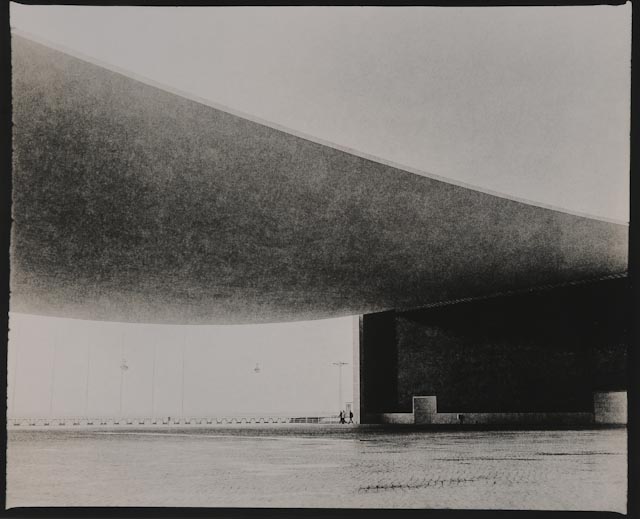

Artist: Jean-Francois Pirson / Brussels Belgium

Space opens up as emptiness in contrast to the earth. On this earth, beings an objects together give shape to spaces. How, in this emptiness, on this earth, should we make our way, inhabit or produce a few material traces, between the movement of beings and objects, between the world and oneself?

An artist and teacher, honorary professor at the Higher Institute of Architecture in Liege, Jean-François Pirson expressives his relationship with space through an array of artistic and educational practices : photography, drawing, installations, texts, walks and workshops.

In the last few years, Jean-François Pirson combines his travels and his walks with his exploratory practices of space and uses photography as a medium to put in perspective parts of the world. Some installations : WE ARE HERE, International Photo Festival, Aleppo, Syria, 2006 ; NOUS SOMMES ICI, La Lettre volée, Brussels, 2007 ; 6th International Biennal of Photography, Territoires, Liege, with a travelling Installation, WASTELAND, 2008 ; DESSINE-MOI UN VOYAGE, The Centro de Artes Visuais, Coimbra, Portugal, 2010 ; SI UN JARDIN PEUT-ÊTRE, Summer of Photography, Brussels, 2010 ; IN THE INFINITE SPACE OF OUR HUMANITY, 11th International Photo Festival, Aleppo, Syria, 2012.

Jean-François Pirson published ASPÉRITÉS EN MOUVEMENTS, DESSINE-MOI UN VOYAGE / DRAW ME A JOURNEY, ENTRE LE MONDE ET SOI – PRATIQUES EXPLORATOIRES DE L’ESPACE, CAHIERS DE BEYROUTH, Brussels, La Lettre volée, 2001, 2006, 2008 and 2009.

“The silence that faces up to things is something I detect in several of Jean-François Pirson’s photographs, in a switch to imagery founded on the physical search for a point of view, the right place to stand, or the place from which to deploy the eye in order to embrace the scope : all the contained space. Photography is essentially immobile, but when infused by walking, it takes on a view of space that is constructed as perception in movement. There is no subject, no centre, but intervals, lines, densities and voids, tenuous forms of continuity, and bodies, beings and their fragile dance, often minuscule, being there at that instant, traces of occupation – or not. How do the things of the world hold together?”

————————–

Sonja Dicquemare, The concrete Passerby, in FENETRE SUR N°1, Jean-François Pirson, Pédagogies de l’espace – Workshops, Cellule architecture, Fédération Wallonie-Bruxelles, Brussels, 2011, p. 175.

Homo Urbanus Europeanus

Artist: Jean-Marc Caracci

http://homo.urbanus.free.fr/portfolio/index.html

The “Homo Urbanus Europeanus” project is about the Man, in the City, in Europe… let’s say about the European “Urban Being”.

Each picture of the project, by the accuracy of its framing and its crisp style, sounds in my mind like a hymn to the magnificent citizen. Indeed, this character who walks, stops and weaves through the city, often lonely but no less proud and determined, is not insane, but rather has the stature of a conqueror. Moreover and according to me, this human presence, this silhouette captured with fineness, always in the right place at the right time, gives the city an unexpected beauty and majesty.

Although primarily an aesthetic work, the “Homo Urbanus Europeanus” project does not hide its political dimension. Indeed, it consists of 31 series, representing 31 European capitals, all photographed in the same style, sober and without any cultural or social visibility, thus favoring the similarity to the difference, the “europeanity” to the diversity. The “Homo Urbanus Europeanus” project is in a way an artistic tool for uniting European countries… whether they already belong to the European Union or not yet.

During 3 years, from summer 2007 to summer 2010, 31 European capitals have been photographed in the frame of the project. Here’s the list :

Bratislava, Riga, Vilnius, Sofia, Madrid, Warsaw, Rome, Ljubljana, Zagreb, Belgrade, Helsinki, Tallinn, Reykjavik, Paris, Brussels, Oslo, Stockholm, Prague, Berlin, Istanbul, Lisbon, Bucharest, Tirana, Budapest, Vienna, Athens, Luxemburg, Copenhagen, Amsterdam, London and Dublin. Istanbul is the only city which is not a capital, but it is nonetheless regarded as the European capital of Turkey.

Artist: Jeanette Groenendaal / The Netherlands

Biography

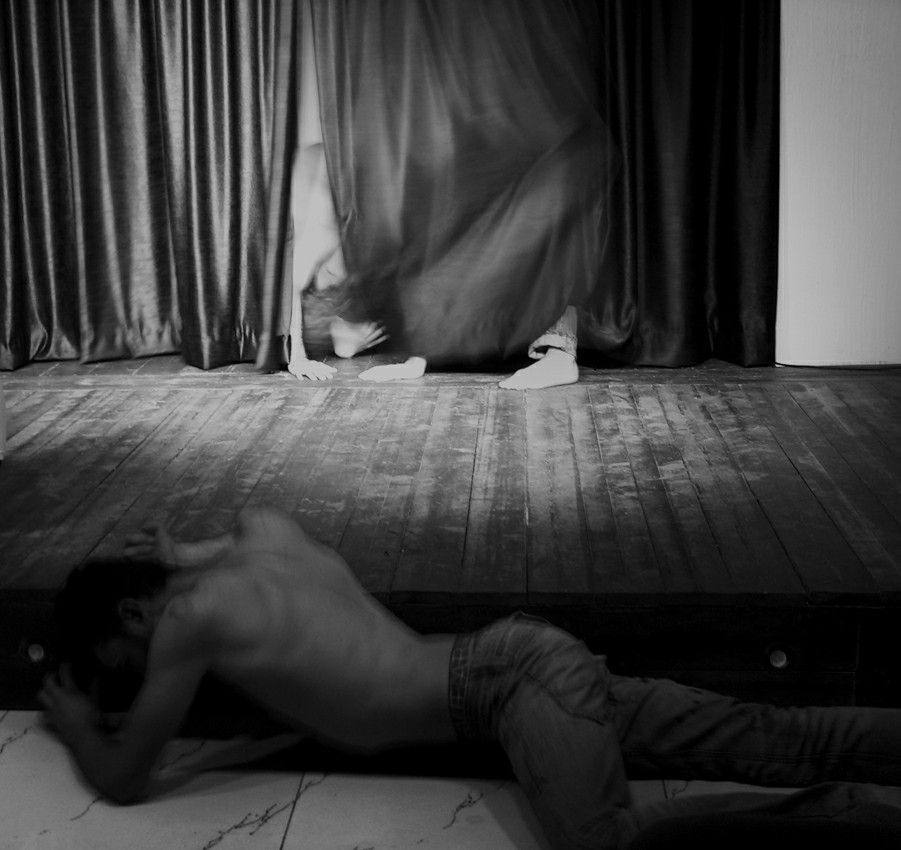

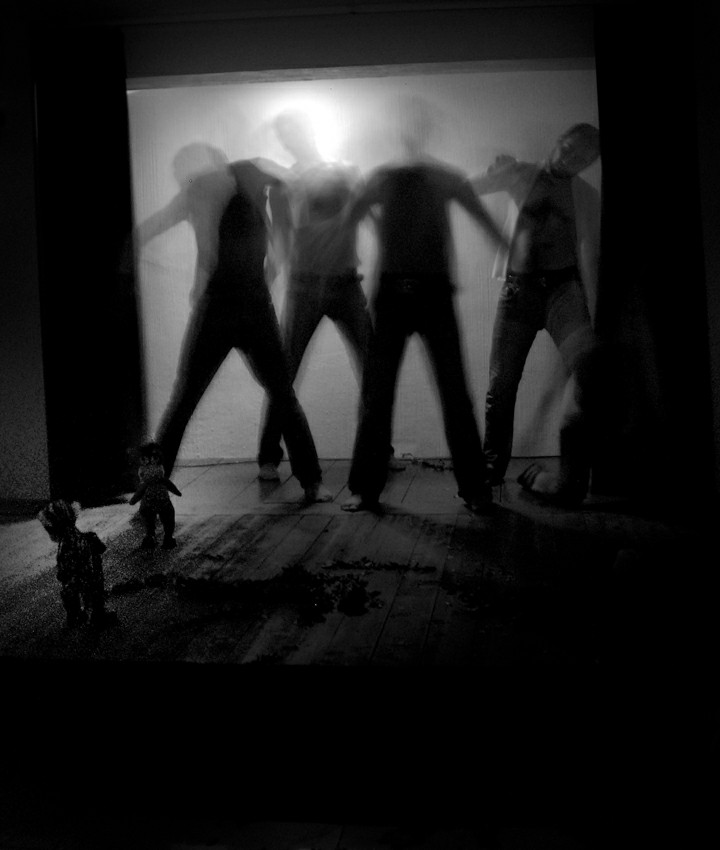

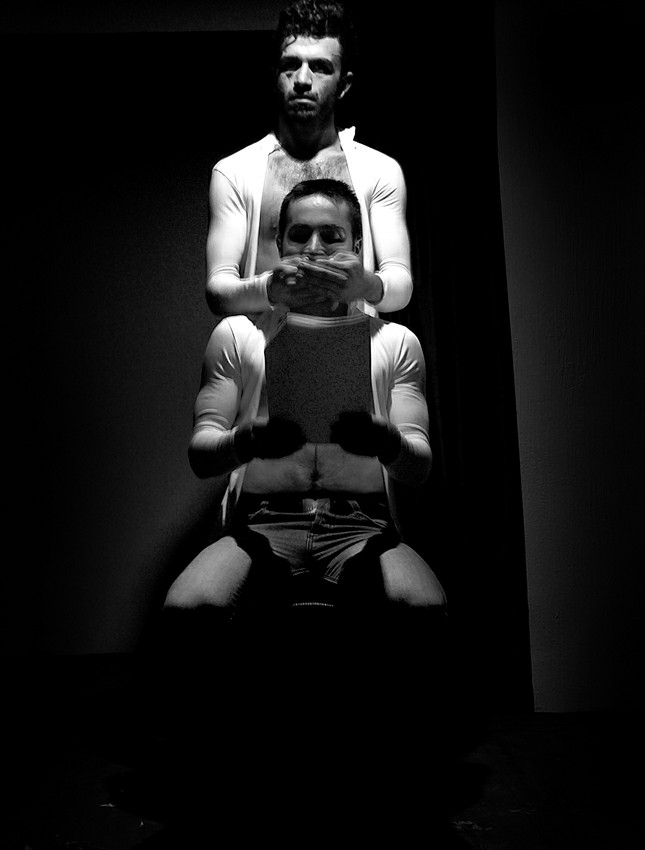

REFORMATION ( English Subtitled)

‘A seductive and furious film essay’, Raymond van den Boogaard, NRC handelsblad

At the age of seven, director Jeanette Groenendaal (Dutch Cocaine Factory, 2007) moved to a deeply religious village.

It was the 1970s, and the girl’s arrival from the city provoked fear in the hearts of the inhabitants of the small hamlet

in the Dutch Bible Belt. They saw her as an “alien” and a “city whore,” and treated her accordingly. The teacher at her

strict Calvinist school called her “Devil’s daughter” and the whole class repeated his words.

Thirty-eight years later, Groenendaal returns to the village to film a personal study of the scapegoat mechanism.

A project staging tableaux performances melting frozen memories on an emotionally charged location. In a series of

‘visions’ she reconstructs, excerpts from her childhood in the village.This stylized flashback is more than a personal

therapy session or a documentary about a fundamentalist community. It returns to the past, not out of revenge or a

need to judge, but to investigate the roots of a past that is returning to the present, with the contemporary outpouring

of religion, conservatism, xenophobia, and judgmental moral standards.

‘How does one group of people who think that they know the truth, what is right and wrong,

how do they decide if somebody else is going to hell?’

Biography Jeanette Groenendaal (1964)

Lives and Works in Amsterdam

Independent Experimental filmmaker

Producer, writer, director, camera, montage, distribution

(Art) Director and Producer of http://www.G-netwerk.nl/;

Art-Science productions, Video Installations, Patricipation Performances

Education: Master of Theatre DasArts, Amsterdam (2006)

Filmanalysis, Filmacademy Amsterdam

Binger Institute; Masterclass editing with Molly Stensgard

Hermetica studies, Illustere School, UvA (2010)

REFORMATION (79’)

IDFA Amsterdam International FilmFestival 2011

Planet Doc Documenatry Filmfestival2012

Reijkjavick International FilmFestival2012

Guanajuato International Film Festival 2012

EYE FilInstituut 2012

Arthouse Tour Holland 201

dOCUMENTA 13 2012

REFORMATION Work in Progress (multiple screen theatre installation)

De Brakke Grond 2009, IDFA 2009, Planet Doc Review 2009, Artisterium 2010

DUTCH COCAINE FACTORY (54’)

DocAlliance/ Ximon Online screenings

(IDFA 2007, subtitled in English Spanish Korean and Polish)

screened in over 10 festivals worldwide and toured Dutch Arthouse theatres

presented with performances and talkshows

Media I Arts I Sciences G-netwerk; in Collaboration with Zoot Derks:

MONT AGE Video Installation, Zoot Derks, IDFA 2011, De Brakke Grond 2011, dOCUMENTA 13

BIOARTCAMP Video Installation, Banff centre of the Arts 2011, Video Poo, WinnipegCanada

TIMELINE CRITICISM with E.S.A, UvA De Brakke Grond 2011

V.A.S.T.A.L series on BioArtist Adam Zaretsky, Waag Society 2010, dOCUMENTA 13 (2012)

DEEP WOODS PCR with Paul Vanouse 2012

Dramayama 2011, 2012

Black Tea Party Erwin Olaf 2010

Inside Out with Jennifer Willet 2008

Dangerous Liasons with Adam Zaretsky 2007

Performances

Jeanne Dark, Eye Filminstituut 2011

EYE MOVES, Eye Filminstituut 2011

Dramayama, Eye FilmInstituut 2011

Initiating art collectives; PATAPOE Artporn- ZootenGenant- G-netwerk

Nominated for the Magic Hour Award, Planet Doc Review, Warsaw

supported by FilmFunds The Netherlands – FondsBKVB- AFK, De Brakke Grond

distributed by; G-netwerk/ EYE (NL)/ Against Gravity (PL)/ INCUBATOR

Artist: Katharina Mouratidi / Berlin Germany

For her series Back Seat Heroes, photographer Katharina Mouratidi portrayed 40 laureates of the Right Livelihood Award. Known throughout the world as the „Alternative Nobel Prize“ it honors people and organizations that have developed outstanding solutions to the most urgent problems of our times and who are fighting for their implementation. 145 persons and groups from 61 countries have so far been awarded the prize. Internationally, it is recognized as the preeminent distinction for courageous personal commitment and social change.

Back Seat Heroes intends to tell the fascinating stories of these people which have found – each of them in his or her very personal manner – possibilities to confront the compelling challenges of the present. The work is a continuation of Mouratidi´s intense examination of international social and political movements, which she is documenting for more than a decade now.

Katharina Mouratidi (*1971), is a freelance photographer based in Berlin. Her photographs are included in numerous collections and have been exhibited in many individual and group shows worldwide, among them: FotoFest Houston (USA), George Eastman House (USA), Lianzhou Photography Festival (China), Rheinisches Landesmuseum Bonn (Germany), Thessaloniki Museum of Photography (Greece), Museo de Arte Moderna Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), Primavera Fotográfica (Spain), Melkweg Gallery (The Netherlands). Since 2009 Katharina Mouratidi is teaching photography at several institutions. 2011 she was appointed a post as visiting professor at Art College Berlin-Weißensee.

Artist: Khaled Hasan / Dhaka Bangladesh

I was born into a Muslim family, and I fell in love with a woman, who is Hindu. I was born in Bangladesh, she in India. When we decided to marry we were engulfed in chaos, our families opposed the match. Our marriage is a social error, politically wrong, they said. But we believed it is not our fault that our families belong to different religions, that they don’t like each other’s religions. We are just two people in love. Isn’t this simple fact enough? I faced death threats, we were on the run for months, and we were stripped of all support. We became fugitives in another country. In the realm of religion we have sinned. They seized the opportunity to punish us, after all we have defiled their faiths, debased their trust in us. Only for religion? We suffered and continue to be separated because of the faith of others. They try to squash our love to prove their devotion to religion. So, what is our identity? Is she still a Hindu and I a Muslim? Haven’t we lost it? Isn’t this rape of our rights, our humanity and our personhood? Isn’t this the death of individuality, thereby death of “them” and also yours? At the funeral of two individualities, I lay confused. Have we embarked on a wrong path or our way is right and theirs wrong?

Since 2008, I have been documenting myself with my photographs. I want to share my inner emotions with others. I am known as a social documentary photographer, but in my social status, I feel, I am not a social human being. I always controlled by the society and religion. I want to be free.

Even after all these, a violent brutal male human character, often rise up through my veins to burst out of my being. Will these tensions break open the shell and usher a new dawn? Or are they just hype, a fake rising, like that of my forerunners? Like other common believers, I have been faithfully following rites and rituals. But agonistic devils try to tempt me, ceaselessly. This endless, nonstop confusion will continue till the end of my existence.

Khaled Hasan, born in Dhaka in 1981, is a storyteller, inspiring people to appreciate and empathize with the cultures and societies he documents. Hasan began working as a photographer in 2001. He has graduated from South Asian Media Academy and Photojournalism (Pathshala). His works have been published and exhibited worldwide. Hasan has worked as a freelancer for several daily newspapers in Bangladesh and international magazines. His works have been published in major magazines and newspapers in the world: Sunday Times Magazine, American Photo, National Geographic Society, Better Photography, Saudi Aramco World Magazine, Guardian, Telegraph, The Independent and The New Internationalist, Himal Southern, Women’s e-News.

Hasan’s documentary project ‘Living Stone’ has won numerous international awards including the 2008 All Roads Photography Contest of National Geographic Society, the 2009 Grand Prix “Europe and Asia – Dialogue of Cultures” International Photography Contest organized by Museum of Photography, Mark Grosset Documentary Prize 2009 and UNESCO’s Humanity Photo Documentary Award 2009

Artist: Leonardo Autera / Italian

An archive of 3,500,000 images, 168 places in the world he photographed. Some 10,000 photographs dedicated to Basilicata, including landscapes, art, architecture and social reportage. As for the rest of its production, they face war, travel, portraits. Autera born in Pomarico (Basilicata) in 1961. He attended high school science in Matera

On a trip to Spain with his fa

ther in 1972, photographing bullfights in Madrid: by this time the MINOLTA iron becomes his companion for life. Buy his first book presented by the photographer PHOTOGRAPHY Belluno Mario De Biasi

drawings by Pierre Michel DECRON DUPUINS of Longanesi & C Editor.

At 16 he left his father’s house by going underground, first in France in Besançon. made his first report on prostitution. Return to Pomarico, where the elderly at the center organizes the result of that report, but the time is still immature for the audacity of that issue, to the point that the scandal broke, the police forcibly raised the pictures from the walls inviting him to abruptly leave the center immediately. Clearly perceive that, unfortunately, there is no place for him and starts to Germany, in Düsseldorf, where he remained until the early ’80s. Freelace worked as a reporter, traveling around the world. Meanwhile, participating in various exhibitions in major Italian cities, French and German.

Artist: Luca Sidro / Italy

This project is an alternative view of Naples.

This is “my Naples”, a city known worldwide today to nearby places like Pompeii and Capri, locked into a stereotype that only talks about pizza, Mount Vesuvius and the music of the mandolin.

A city portrayed in the past by several photographers, including foreigners, who have always emphasized only the folk side: The Vesuvius, small crowded streets, the clothes hanging from the balconies, the Mafia.

This is an alternative narrative that begins with a single shot, emotionally, without the need to tell a fact.

A mediterranean style inspired by forms, shapes and colors.

An instinctive and rational approach at the same time.

I print these photos on fine art paper Hanemuhnle photorag satin, in a small format 13cm x 13cm and note a title with a pen on each photo.

Artist: Marcin Andrezejewski / Poland

In defining the modern metropolis known as the Shangri-La, Marcin Andrzejewski provokes. Encouraged to reject the mundane meanings, which filled in the daily hustle and bustle of the concrete beast. Shangri-La is the world of literary non-existent. “The land of the harmony and wisdom” which is so urgently needed. If the art would mean nothing but emotional triggers,

the land of imagination, the agreement will remain an intimate space with the viewer. We understand it, each individual, the ability to experience life, but the overriding feature is that the boundaries of the land rover in excess of Shangri-La, was banned from leaving. This is the provocation – the superiority of the image over literature, as well as the ephemeral life. Who will feel the taste of photography, to leave this magical land will not have the slightest need.

Marcin Seweryn Andrzejewski was born in 1977 in Drezdenko, Poland. Member Gorzow Photographic Society and the Association of Polish Art Photographers. Graduated from Higher School of Photography in Jelenia Gora in the studio of Wojciech Zawadzki. He is a photograph based on classical techniques. Since 2005 he lives and works in London.

Selected solo exhibitions:

1996 Warszawa, Galeria WIPH,

1996 Gorzow Wlkp., Mala Galeria GTF,

2000 Wroclaw, Piwnica Stanczyka,

2001 Krasiczyn, Galeria ARP,

2001 Gorzow Wlkp, Mala Galeria GTF,

2002 Gorzow Wlkp, Mala Galeria GTF,

2002 Ostrowiec Swietokrzyski, Galeria Browar,

2003 Jelenia Gora, Galeria Korytarz,

2004 Groningen, Light Zone,

2004 Wroclaw, Galeria ARP,

2010 Gorzow Wlkp, Mala Galeria GTF,

2011 Szczecin, Fotart.

Artist: Mariam Amurvelashvili / Tbilisi – Georgia

http://www.amurvelashvili.gr

Dukhobors in Georgia

The intention of this project is to represent the group of Dukhobors’ ethno-religious minority who were exiled from Russia to Javakheti region in 1841 and settled there as small communities.

It was a mystical religious sect that separated from the Russian Orthodox church in the

1950-90s.

Traditionally, Dukhobors reject all types of religious and secular authority.

Hence, mankind does not need any intermediaries (priests) between themselves and God. Religious symbols such as churches, crosses, liturgics or icons are not necessary since they are constructed by mankind. God is an incomprehensible essence – an inner light – that exists in every individual who expresses love, and therefore, all human beings are by definition equal. Sin is not inherited in Dukhobor belief, and every person has to repent the sins he or she commits.

The subject of great interest is the way how Dukhobors follow their traditions. Social rules specific to Dukhobors are often taken into account. When it comes to funerals and weddings, their traditions seem to be strictly upheld. They are dressed in traditional clothes.

The origin of Dukhobor movement goes to provinces Tambov and Voronezh in Russia.

The first known leader of the movement was I.Poborikhin, who was then arrested and exiled to Cyberia. Dukhobors were persecuted both by the state and by the Orthodox church. In 1835-39 years special commission concluded that sectarians were destabilizing the foundation of Russia, as they denied the authority of religious and secular leaders by refusing to do military service and pay taxes.

. Consequently an ultimatum was given to sectarians: convert to Orthodoxy or leave for the newly conquered Caucasus region. Most of them decided to go into exile

In 1839-45 Dukhobors settled in the two Georgian regions of Javakheti(near Akhalkalaki) and Dmanisi(kvemo Kartli region). Settling in the Caucasus had some advantages for the Dukhobors and other sectarians: they were freed from religious persecution, got exempted from tax duties and military prescription. Nevertheless, the resettlement in Javakheti was difficult.. Thousands of Dukhobors died from starvation, epidemic and economic destitution. Survived founded eight villages – Bogdanovka, Gorelovka, Orlovka, Spasovka,Tambovka,Efremovka, Troitsovka and Rodionovka.

Dukhobors were strictly isolated in their boarders and these boarders were mental demarcation of their homeland “dukhoboria” not only for Dukhobors but also for their neighbours. Since 1989 partly because of ethno-religious and partly of socio-economic reasons ,Dukhobors began to leave for Russian Federation. But they couldn’t resettled there in compact communes, therefore it became difficult for them to preserve their identity.

Dukhobors are not numerous but very interesting ethno-religious minority in Georgia. The aim of my work is to show Dukhobors’ customs, religious services, traditional rituals,everyday life, those who still stay in Georgia, in Javakheti region, where they have lived for 150 years and managed to preserve their originality and identity.

Artist: Marwen Trabelsi / Tunisia

Marwen Trabelsi is a Tunisian photographic artist:

After an academic career in art and communication, he exhibited and participated in many photographic and cinematographic festivals in Tunisia, Germany, France, Italy, Cameron, Nigeria and Morocco…

His photos and movies have earned many national and international prizes as the first prize in Festimed Mediterranean festival of photography and the ‘coup de coeur’ prize in the 18th session of the pictures and sounds Festival in Pontivy Morbihan in France 2011. “

Spring become winter

Artist: Mohamad Manjoneh / Syria

TV WARS

Artist: Monika Anselment

This work consists of a series of photographs that I have been taking in front of my television set. The photographs are all the same size (57cm x 80 cm). They are lambda prints made from 24/36mm negatives or slides, and have been mounted on dibond with gloss lamination.

1

The photos depict acts of violence in various countries, including Afghanistan, Iraq, Yugoslavia, Palestine and the United States. The majority of the images have been photographed from news programs, while others have been taken from documentary reports. I have chosen television as a medium for this project because it is universally and internationally understandable. As we have all been exposed to so many similar images, anyone who has a television can understand these photographs and knows that they depict acts of violence.

We are regularly served these wars on television in a miniature and easily digestible form at dinnertime. The extent of this military violence has been reduced here to its smallest possible expressive form – t o a n i m a g e.

My photos all share one thing in common. They are all very beautiful – some are even kitsch. In this series of television images, we are no longer able to distinguish unambiguously between “good” and “evil.” The fascination with violence radiates simultaneously from all of the photographs.

On a purely phenomenological level, we can recognize various elements in the individual photos. In one, we see an explosion over a city, in another, a colorful burst of light. Here, we find a sunset, there, a column of smoke in the mountains.

I find the landscapes in these photographs aesthetically stimulating – they are literally beautiful. They remind me of the genre of landscape painting. When we look at the photos, we immediately perceive that they are beautiful, but we know at the same time that they are representations of death. This ambiguity prevents us from immersing ourselves in the incredible beauty of these landscapes.

The photos present the fascinating side of political violence. It is a fascination that we experienced as children when we knocked over play towers or detonated explosions with chemistry sets. Here, however, it occurs on a scale of which we never dared to dream. Now we are confronted with this fascinating violence as a reality, as an apparently legalized reality. Only upon reflection do we realize that the bright lights and the fire mean destruction and death. Yet despite this reflection, the images retain their fascination.

The effects of war on the world are always destructive. At home in our apartments, however, they are presented on our television screens as beautiful, as a colorful fireworks located far away and with a beauty that is supposed to fascinate us.

Because the fascination of these spectacles is so powerful, it is only with great effort that we are able to draw an intellectual connection between these images and the bloody, deadly consequences of the violent acts they depict. Even when we are presented afterwards with images of dying people, the real human suffering remains abstract and removed.

In my photographs, we see that political violence in the media is staged as a spectacle. In Afghanistan, columns of smoke and exploding bombs form a dramatic stage set before towering mountains. In Iraq, we are presented with a sky full of fireworks and balls of fire. In Yugoslavia, we see not only refugees (whose fates are supposed to convince us of the war’s justness) but also burning refineries and the illuminated night sky. In Palestine, balls of light shoot across the sky. In New York, where the best-staged spectacle occurred, the tallest skyscrapers in the world collapsed after being hit by two flaming airplanes.

2

Television works exclusively with the medium of film, i.e., television viewers see moving images. Photographs, however, are still images. The photographs presented here have been congealed from moving images on television. In television news, the images change quickly. Over the course of just a few minutes we are confronted with a vast diversity of issues and events. The images race at an incredible velocity from one issue to the next, and we have no time even to gasp for air or to recover from the shock in any way. Images of starving or freezing refugees are directly followed by images of the goals scored at the latest football matches.

When these moving pictures are reduced to still images – photos –, we are suddenly able to sit back and exhale. We have time to look at what we are being shown. We are allowed to pause for a moment, to observe, to register, to reflect and to question.

When television images are brought to a standstill in the form of a single photograph, they become less sharp. We see that the image consists of individual dots that are created by the impact of electrons on the television screen. By reducing the camera speed, I have increased the lack of sharpness in the photographs. Both of these effects lead to an estrangement. In addition to the individual colored dots (which again is a play upon the tradition of painting, in particular, of impressionism), we see a variety of colored stripes. These estrangements are confusing and disorienting. Television news usually consists of sharp, precise images that symbolize objectivity and authenticity. Now, however, we are confronted with these disruptive factors: stripes, pixels and logos. These disruptions remind us that the images have been produced for a particular purpose, that they are not simply reproductions of reality. The estrangements also make the photos more abstract. We do not immerse ourselves in them; we do not partake, as it were, in their internal life. Rather, through this abstraction, we are held at a distance. This distance enables us, in turn, to approach the occurrences depicted in a new and more reflective way and to raise our own questions about the images.

Abridged version of a lecture at the University of Leipzig on 10/1/2003

Monika Anselment

Translation by Tom Lampert

Artist: Nathalie Daoust / Canada

Impersonating Mao

Photography by Nathalie Daoust

Supported by the Canada Council for the Arts

The work of Montreal-born photographer, Nathalie Daoust, maps the blurred boundary between reality and imagination to explore ideas of fantasy and escape. For her new project, ‘Impersonating Mao’, Daoust focuses on the interior world of an impersonator who assumes the appearance and bearing of Mao Zedong, founder of the People’s Republic of China. Daoust’s portraits record her subject’s desire to flee reality and take refuge in a dream world of half-truth and illusion.

When Daoust first met her subject in 2008 – posing as Mao in Tiananmen Square as an act of personal homage – she was intrigued by his construction of an alternate identity from the iconography of his country’s troubled past. In 2010, she returned to Beijing and photographed the impersonator extensively, both in a domestic setting and at sites of historic importance. The juxtaposition allowed Daoust to interrogate communist China’s complicated relationship to Mao’s legacy, echoed in the internal negotiations of the impersonator as he transformed into Mao.

Shot on a stash of old Chinese film uncovered in Beijing, Daoust physically manipulated the negatives in the darkroom to create a dreamy mood of memory and illusion. Each print is sealed in amber-like resin; the resulting portraits combine a 21st century handling of perspective with a visual timelessness, reflecting Daoust’s preoccupation with the borders between contemporary reality and an imagined past.

-Louise East –

Nathalie Daoust’s photographs reflect a love for random places and a wild, inexhaustible sense of inquisitiveness. Exploring, experiencing and documenting rarely visited landscapes and carefully hidden hotel rooms, Daoust spent the last decade producing voyeuristic insights into these otherwise veiled existences.

The Canadian Daoust, who studied the technical aspects of photography at the Cégep du Vieux-Montréal, spent two years in the late nineties living in the Carlton Arms Hotel in New York. The rooms, all themed and decorated with wild, colourful murals formed an excellent background for Daoust’s photographic projects which focused on the dark, obscure and, especially in those years, the ghostly. Daoust has traveled extensively and took photos not only of New York hotel rooms but also of Tokyo’s red light district, Brazilian brothels and Swiss naturists populating the Alps.

Daoust has created an oeuvre that is both diverse and intense. Seeking to translate her almost childlike curiosity, her perseverance and her highly individual interpretation of the world into fairytale like stories, Daoust single-handedly creates new myths about modern day society, as well as real-life stories of the underdogs.

– Georgia Haagsma –

Artist Statement

Since my very first experiments in photography I have been fascinated by human behavior and its various realities, by the ever-present human desire of living in a dream world. The aesthetic of my new project continues this visual exploration at the border between dream and reality, yet this time embraces personal escapism and the act of loosing oneself.

My objective as an artist is to push the boundaries of photography through experimental methods, working with new mediums and discovering new techniques in the darkroom.

Two weeks in Homs /Short Movie

Artist: Nathalie kardjiane / Syria

Before March 2011,Homs was a city famous of jokes ..

Since one year, after having thousands of the refuges who trying to find a new home… no one remember the fun of Homs It becomes a symbol of tragedy. We lost fun, we lost happiness,

They left their home with hundred questions in their minds; they don’t know who and why was shooting …they were only knew one part from this conflux

” about the peaceful demonstration in the beginning of the problems

I stayed in the beginning of the crises in Aleppo city

. I was trying to make my self busy for not thinking about what happing in my home town , but every weekly phone call with my parents and friends I was shock with the bad news and End my day very sadly…

April 30 – 2012

The missed news about my uncle from 20 days ended with a phone call from my mother saying that they found him killed, I shocked and decided to take the risk and hit the road with the hope to be a wrong information.

All family went to distinguish my uncle body from the other corpses in the military hospital and in the way to there we pass by my school building which was unfortunately completely destroyed.

Recognizing the body was easy because of his broken pinky finger. Otherwise the rest of the body was deformed…

Every thing changed for ever…and we don’t know how Homs will be after crises…

And in that two weeks I felt I lost my home I lost my neighborhood I lost my school I lost Homs city

Nathalie kardjiane / Syria

Born in Homs, Syria 1988 lives and work in Aleppo .

Nathalie kardjian graduated from the University of Fine Art in Aleppo year 2010..

2012 she was one of the fonder of Art camping successful activity in Aleppo during the Syrian crises with Le Pont organization in Aleppo city ..

“ Two week in Homs “ her first Documentary movie about personal experience in Homs / April 2012

Her Movie will be part from Aleppo International photo festival 2012 in Aleppo /Syria

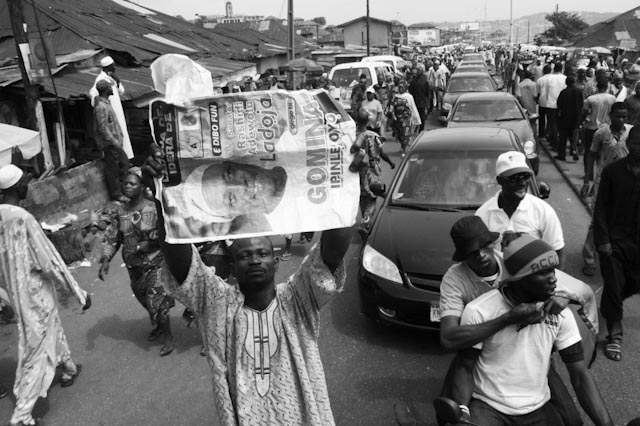

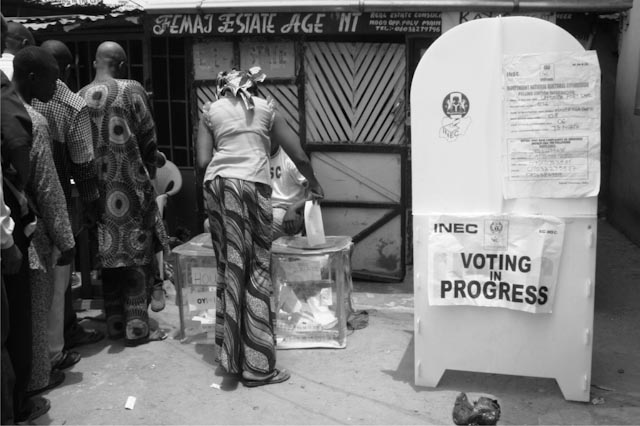

Artist: Nseabasi akpan – Nigeria

Born 1978 in Ibadan, Oyo State, Nigeria. Nseabasi akpan is a freelance photographer with a passion for reportage and experimental documentary; he has been working as a photographer since 2004.

In 2010 he won the African Artists’ Foundation Award and he won the European Union/African Union Photography Prize in 2011. His works have been published by the BBC Focus on Africa Magazine (London), Jeune Afrique (Paris) as well several print and electronic media in Nigeria.

Nseabasi’s work has been shown in art exhibition in Nigeria, Ghana, Ethiopia and Croatia.

Artist: Photo By Luca Sidro

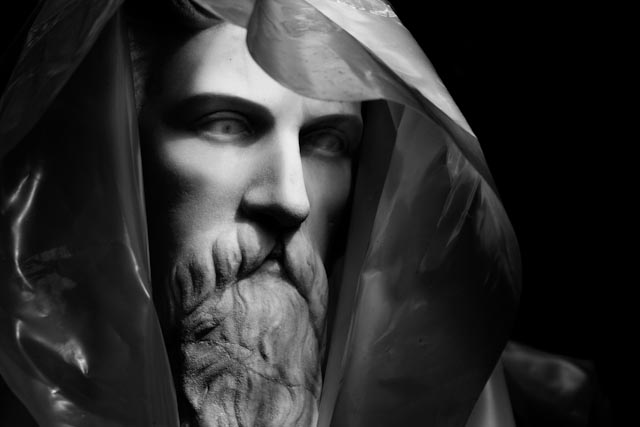

Artist: Ploutarcos Haloftis

During the restoration of the park near my house , I saw a statue , wrapped with plastic .This reminded me somehow the works of Christo . At the same time , the way shadows and light were playing on the new surface , gave me the impression that a new sculpture had accidentaly been created . Many walks and many full memory cards later , I ended with a body of about 25 “ final “ photographs . It was about time : some days later the restoration ended and the statue took its initial form again .

Ploutarcos Haloftis

Artist: Roger Colombik Bruce

Roger Colombik Bruce

My work as a photographer reflects my research in the development of civil societies. Rooted in the tradition of documentary studies, the projects are presented in contemporary formats that include large-scale photography (banners), video, writings and intervention. The works are often presented in public places to achieve a maximum impact for community discourse on important issues. My projects are collaborative for I strongly believe that working with young artists from a given community provides for a more genuine reflection about that community. (And a much richer experience for myself.) A recent project is Sacar Adelante (To Bring Forward) and involves working with childhood development agencies in Ecuador. These programs enable children to come off the streets and into a situation where shelter, security and education are provided without any heavy handed religious indoctrination. This project is ongoing and is intended as an open source program to be utilized at similar developmental programs throughout Latin America. Another new project just underway is Dem Dritten Das Brot! (To the Third-Bread) that examines issues of cultural heritage and migration with ethnic German communities in western Romania.

Life born in a Slum

Artist: Saikat Mojumder / Dhaka Bangladesh

Sajila is a working mother living in the Korail slum in Dhaka city. She has her husband, mother-in-law and three children (two daughters and a son) in her family. Her husband cannot afford all the maintenance of the family alone, Sajila works as a day labourer to support him.

The story begins when Sajila is expecting again. The poverty-ridden family could not be happy with the possibility to have the family even more extended; nonetheless, Sajila continues nurturing her hope to have another male-child this time.

Quite understandably, it was not possible for Sajila to have the extra care or medical support an expecting mother should get. The family will starve if she does not work, so she continues with her heavy work as a day-labourer. This was definitely the last thing a pregnant woman should go through.

However, I began my photo shoot on Sajila when she was four-months pregnant. She lives in a small, suffocating and unhealthy room in the Korail slum, which is surrounded by lake. As it is in most of the slums, there is also no doctor or medical service available here in this slum. There are indeed some midwives helping the pregnant mothers in the slum though. But their ability is very much questionable and giving birth to a child under their supervision is unsafe, it even leads the mothers and children to death often.

The reason behind the high death rate at childbirth is most of the childbirth in our country is maintained by untrained midwives.

Due to economical insolvency and lack of proper medical service, Sajila also decides to give birth to her child under the supervision of a midwife. Sajila believes, if she has God by her side, she will make it safely, for all her three children have been born this way.

Her economical condition was even worse during her pregnancy and she even had to starve for several days. Even though, Sajila did not forget to take advice from the midwife about the dos and don’ts. Finally on the due date, she gives birth to her child under the guidance of that very midwife. Without any modern facilities or medicines, in an unhealthy atmosphere, Sajila has her baby boy delivered normally. It might sound incredible to many, but Sajila walks herself home with her son only after an hour

Artist: Scott Typaldos / Lausanne Switzerland

Scott Typaldos was born in Lausanne, Switzerland in 1977. He lived in Belgium from 1991-1996, then passed through England, France and then the United States for 5 years. It is during these years in a filmmaking school that he became familiar with the basics of photography.

In his first years, Scott’s photography was centered around his personal life and themes such as initimate, street and travel photography which he continues to photograph until this day.

In the Spring of 2007, he worked on his first documentary In Gabon. He photographed the oil searchers of the Lambaréné region. His focus was on the worker’s inhumane treatment and their slavelike working conditions.

In 2009, Scott travelled to India photographing different slums in the most high tech Indian city: Bangalore.

In 2010 He started working on the animal condition photographing in the pathological department of the Bern Tierspital (Switzerland)

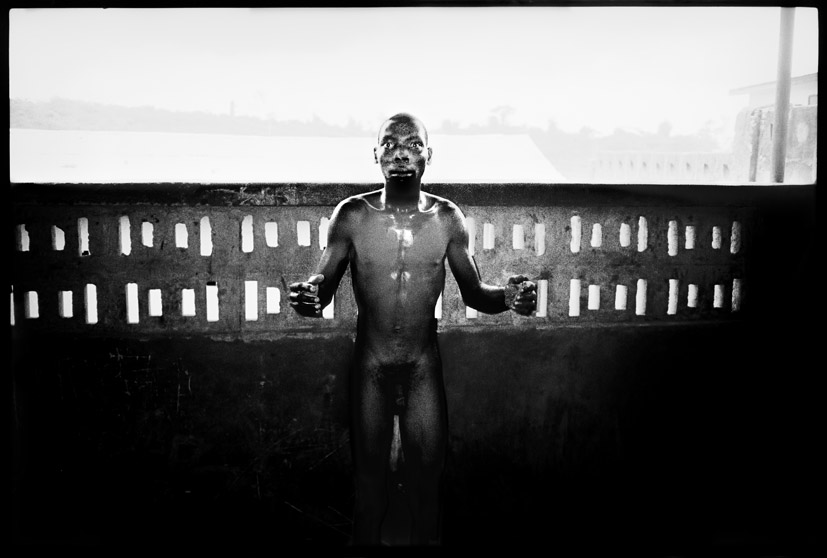

In 2011 Scott moved to Ghana/Togo where he studied and photographed the countries’ infra structures for the mentally ill in addition to the local funeral rites.

In 2012 He is pursuing his research on the mentally ill extending his interest to Eastern Europe and pther African countries.

I call myself a documentary photographer although I sometimes feel uneasy when categorized in this manner. Most photographers who have influenced my work are in a documentary tradition because their focus is on reality, human beings, their bodies, faces, the social or economical conditions they find themselves in. Whether subjectively interpreted or not, I feel that their raw material comes from a a reality that leaves traces. Documentary photography has a certain smell that I like my work to have.

On on a more personal level I sometimes I think of photography as Winnicot’s transitional object: An object you create that fills a void or empties space. An object that has no function and means nothing but is affectively charged. Though this object is useless, it is important in channeling existential traumas and creating an abstraction out of a nerve noisy reality. For some photographers, it is about being there fully in reality and being compassionate. It is also about feeling and capturing an essence. To me it is about re experiencing an awkward distance. Something happens when you photograph a human being and know that you should be compassionate. You know the situation asks for a stronger link but your breathing is calm and steady.You ask yourself questions why this ambiguity exists. What are the ways that you have to relate to others. If the distance is strange and in my case I feel it is, you work around the coma and you ask yourself why you do not care. The truth is that I am like most people who grew up looking at pictures and films of the 80’s ethiopian famine, I am used to them and find no way to relate to them. The only thing I need is to see them for myself. Pictures allow you to know something exists but do not replace the act of seeing for yourself. So I started a quest of putting myself in connection with hardcore pain and difficult life conditions. I wanted to know if it ever would wake me up from my emotional inertia. When will I finally be able to realize the level of pain someone else feels without automatically censoring it to the dark depth of my soul. I do not feel it is my role to be ethical. I am not a judge, a policeman or a politician. I prefer to come close to human perversions and in this respect, I would call myself a very unethical photographer. I have taken picture of pain charged humans without the slightest intention to save them or help them. I could have played the trauma or guilt game that a lot of photographers like to fool profanes with but in truth I get a kick out of helping people scream on my pictures. When their pain is on my pictures, my anger is with them but not in me. The more the pain is captured in its essence, the more the picture gives a voice to my anger. Naturally my anger is nothing compared to their pain and I should be at their service canceling anything I would possibly want to express. That is why I am highly unethical. I use people’s pain to express myself. I take pictures to make people feel all sorts of bad stuff when I could very well accept things as they are and let people live peacefully.

Perhaps that a human being was first made to survive and then to link. It is the range in which the crocodile state (our reptilian surviving roots) and the social animal must coexist. Ethics are optional. Knowing one’s self is more important.

The Liberace Of Baghdad

Artist: Sean McAllister / United Kingdom

Sean McAllister background

Sean McAllister left school at 16, worked in a variety of factories in the North of England before he picked up a camera and filmed his way into the National Film School, where he graduated in 1996. His first film, Working for the Enemy BBC2 (Mosaic Films) was nominated for a Royal Television Society Award, 1997. Sean followed up with The Minders (BBC) earning him another Royal Television Society Award Nomination, 1998. After these came Settlers (2000) and Hull’s Angel in 2002.

From his early films to his more recent international successes, Sean McAllister’s films portray, with characteristic intimacy and frankness, people from different parts of the world who are struggling to survive but are survivors, caught up in political and personal conflict, trying to make sense of the world we live in.

Sean’s recent films include The Reluctant Revolutionary (2012, with the Irish Film Board ), Japan: A story of Love and Hate (2008, Co-production BBC Storyville, NHK, Ten Foot Films Ltd) and highly praised The Liberace of Baghdad (2004, Co-Produced with BBC Storyville, TV2 Denmark, Ten Foot Films Ltd) which received the Sundance Film Festival 2005 Special Jury Prize Winner amongst numerous other awards.

The Liberace Of Baghdad

Held up in a heavily fortified Baghdad hotel the pianist, Samir Peter and the film-maker Sean McAllister try to survive the “peace” of post-war Iraq.

Samir Peter, once Iraq’s most famous pianist now plays in a half-empty hotel bar to contractors, mercenaries and besieged journalists. In his heyday he described himself as the ‘Liberace of Baghdad’ but today he sleeps in a bricked up hotel room, too afraid to cross town to his 7 bedroom mansion. His string of western girlfriends has led to his wife and two of his kids leaving for the States.

But now Samir has a visa to live in America too, to find fame and fortune there is what he calls his ‘one last adventure in life’. But Sahar, his pro Saddam daughter hates America for what it has done to her country. She refuses to go and Samir is set to leave alone.